It’s not often that we’re grateful there’s a general election in the offing, but this week it’s provided an absolutely fantastic example of the power of Facebook, when it’s used smartly. The example comes from one of our UK political parties, but the principles absolutely apply to any organisation.

Initially, my eye was caught by a story about the Conservative Party spending over a hundred thousand pounds per month on various advertising and promotional activities on Facebook.

Invoices obtained by the BBC apparently show spends of £122,814 in September 2014, and £114,956 in November:

(Click the image for the full story on the BBC website).

So clearly, that’s a lot of money, but that’s not the really interesting thing about the article. Further down, a digital expert who’s quoted as currently working with the Labour Party on their online marketing, says

“I understand that the Labour party has been spending less than £10,000 a month on its own Facebook presence”.

Now, the spin provided in the article is simply that Labour spend less because they don’t have the resources that the Tories do, due to being linked with fewer (they imply) evil millionaire megalomaniacs stroking white cats in their mountain lairs. Or something.

But then I remembered something that had been very viral in my personal Facebook feed lately, and wondered if possibly the story was slightly different.

I wondered if, perhaps, the Labour party don’t NEED to spend anything like that amount, because they’ve come up with a clever way to use Facebook which ensures that their content spreads organically, AND they are able to collect voters’ email addresses (one of the elements that there was a line item for in the Conservatives’ invoice) without any additional cost.

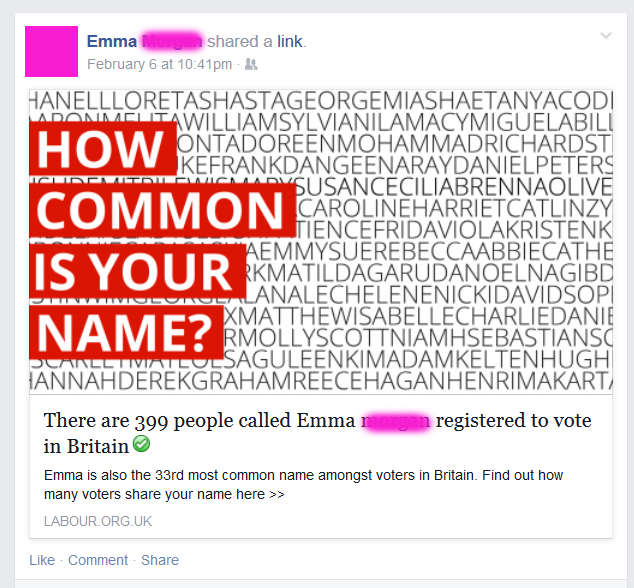

Maybe some of you have seen this in your Facebook feed? It’s been anonymised to protect the privacy of the originator:

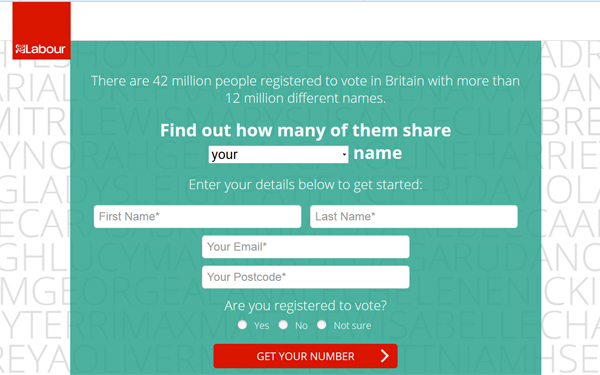

Clicking on that newsfeed item takes the user to a website which looks like this:

Are you seeing how this is working, yet?

Person A publishes their “how many people have my name” result, and it appears in Person B’s feed, because they are Facebook friends.

Person B fancies getting their result, so clicks on the newsfeed item. On arrival at the website, they’re invited to hand over some minimal but important personal information*, and once they have “their” number, they are able to post that back into their own Facebook feed.

Whereupon, presumably, persons C and D notice it and decide to click and…you get the idea. Viral in its purest form.

And because it’s organic (ie, friends are sharing it with each other, voluntarily, through their news feeds) it won’t be costing a penny. There will almost certainly have been some initial spend in order to get the ball rolling – presumably where that 10k per month comes in – but unlike the Conservatives, Labour aren’t reliant on putting the pounds constantly into the top of the Facebook slot machine in order to get those all important email addresses out of the bottom.

The perfect viral storm on Facebook

All credit to the Labour party here, they have thought through every aspect of this process, and exploited the Facebook environment perfectly.

The basic concept (finding out how many people with your name are registered to vote) is simple but clearly catchy enough for many people to bother engaging with.

The website is carefully designed so that you fill in your details as quickly as possible in order to get your result.

And the graphics and text which go back into the user’s newsfeed with their result, speaks directly to the next batch of contacts (“How common is your name?“, not “I found out how common my name is” or something similar).

Impressive, right?

*re that personal information: here’s the small (really quite small) print from the bottom of that webpage. Assuming you read beyond the big red “get your number” button because, yeah, we all do, right?!

Simple, powerful, unique

If this one example isn’t enough to convince anyone out there of the kind of power that clever use of Facebook can unleash, nothing will. Let’s look at the resources used: A simple, one page website capable of collecting some basic information. A feed from publicly available electoral roll data. Some creativity to tap into people’s curiousity about themselves and their names. And access to the single biggest concentration of UK citizens, and their social ties, that has ever existed.

Leave A Comment